On 3 December the OECD released the latest PISA results; their assessment of 15-year-old students in reading, science and mathematics across 79 countries. PISA is high profile in many countries, so system leaders often have to respond in some way; the pressure builds to announce a large policy change.

The policy discussion surrounding PISA is characterised by large policies, broad objectives and big issues. There is a focus on foundational skills, digital technology, equity and excellence, growth mindsets and so on. These things are all important but they encourage policy change rather than strategic reform; there is precious little discussion of the tangible steps a system leader can take to improve reading, science and mathematics performance in their system.

In this blog I want to share an approach that contains tangible steps that I have seen prove valuable in a number of systems. Ironically, it reflects the policy development approach of many high-performing systems in PISA even if it is rarely a part of global policy-discussion. This approach will enable system leaders to identify immediate reforms while also laying the foundations for more targeted and efficient policy change.

An approach targeted to system needs

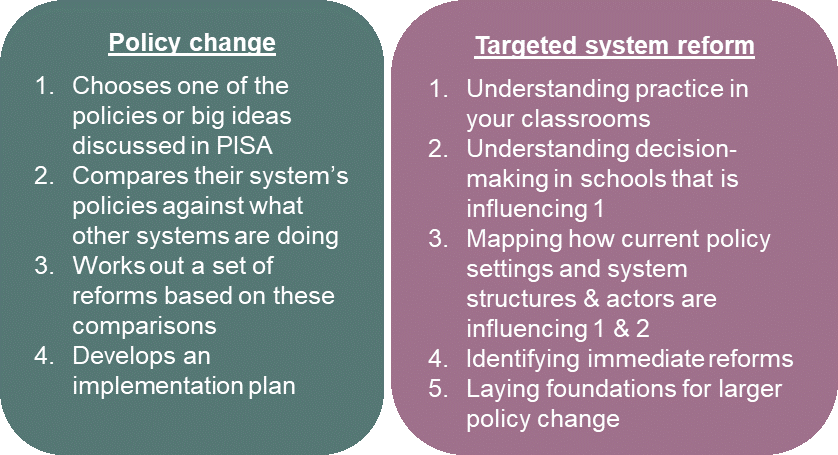

To illustrate the broad difference in this approach we can compare a ‘policy change’ approach with the steps I am discussing in this blog that I have labelled ‘Targeted system reform’. As depicted in the below figure, each approach sees system leaders undertake a few key steps.

Time and again I have seen system leaders pushed into large policy change that is disconnected from what is needed in classrooms in their system. It often starts with choosing a policy area for reform, undertaking some international benchmarking and then thinking about sequencing and implementation in a system.

Though this process will facilitate an interesting discussion, it rarely improves outcomes because it is not anchored in the needs of your schools and classrooms. The process doesn’t touch schools until the implementation phase – creating a large gap between policy design and implementation. And the larger this gap, the more likely the policy will fail.

Don’t get me wrong, we need to look at global best practice. There is much to learn from the successes and failures of other systems. And in some cases there is a clear ‘gold standard’ to follow. But we don’t start with the gold standard. We should always start with what is needed in schools and classrooms in your system and then develop reforms from there – drawing on research and global best-practice and bringing in elements of the gold standard that are applicable to your system.

Below are some tangible steps that follow a more targeted approach. The approach identifies some immediate reforms for quick implementation while also laying the foundations for bigger policy reforms.

Understanding practice in classrooms & decision-making in schools

PISA assesses reading, science, and mathematics, so we need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of current practice in schools and classrooms in these areas. We need to address some fundamental questions so we can properly respond to the PISA results, including: What are the most common textbooks used by maths teachers? How many primary school teachers are using evidence-based reading programs? How are biology teachers assessing what students have learned about living cells? These questions go to the heart of what determines performance in PISA.

We want to understand what is happening in classrooms and the decision making in schools that impacts:

- What is being taught?

- How is it being taught?

- How is it being assessed?

We need to collect this information so we can identify the best way to support teachers and schools to improve. Some systems will be able to answer these questions reasonably easily. But most systems I work in don’t have these answers – or at least all the answers. A senior leader in a system we work with that has taken this approach recently said:

“We always think we have an idea of what is happening in schools but now we know for sure. Some of the data confirms what we thought and some surprises us, but the detail always helps us design and implement our next steps to really impact schools”.

Collecting this information doesn’t have to be difficult and time consuming. Of course, if you want comprehensive data covering all schools then it will take a while. But when we do this work, we use surveys, focus groups and school case studies to quickly paint a reliable picture of what is happening in a system. As always, there are trade-offs between the optimal coverage and the resources and time available. We often find that after several carefully selected and planned school visits the main trends quickly emerge and the findings repeat themselves – the problems and uncertainty is the same across schools, the strengths and weaknesses emerge more consistently. So, it probably won’t take too long before you can feel confident developing the right system response.

Analysis of the data collected from schools needs to focus on the three questions above. Therefore, it needs to identify the common curriculum and instructional resources implemented in the system, including analysis of learning tasks and activities and lesson and unit plans. And this should be complemented by observations of classroom practice to better understand the teaching practices employed in schools and how they connect to the instructional materials used.

For systems that are tight and prescriptive on their curriculum and instructional resources then this process is really about curriculum implementation. For systems with, for example, prescribed textbooks, sequenced learning activities, assessments and detailed curricula, the analysis focuses on how this curriculum is used in classrooms.

However, most of the systems we work in are not tight on their curriculum; they offer schools and teachers considerable autonomy to choose the instructional materials they use in classrooms (usually within a curriculum framework). So a common finding when we do this work is that there is large variation in the quality of instructional resources being used and that it is unclear how school leaders and teachers should decide which instructional resources are the best ones, when they should be used, and in what sequence. In short, teachers generally tell us they want more support and guidance choosing and implementing quality teaching programs. This leads to a very tangible policy response to PISA results.

When it comes to assessment, it is useful to document the strengths and weakness of assessment practices in schools in reading, science and mathematics. We regularly find in systems that there is a lack of clarity around assessment moderation and what school leaders and teachers are supposed to do. School case studies often highlight a lack of expertise on effective assessment, uncertainty about how summative and formative assessments should be used, and varied implementation within and between schools. Systems we have worked in have responded by providing clear assessment guidance and common assessment tasks and samples of student work to support schools to develop and use summative and formative assessments. This has been more effective when they have been coupled with greater role clarity for people in schools to improve the quality and use of assessment data.

At the end of this analysis you should be able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of practice and decision-making in schools about the three questions above. With this, you should have a very good idea of the concerns of teachers and school leaders and how to better support them.

Mapping the impact of current policy settings and system structures & actors

Complementing data from schools is a mapping exercise of how current policy settings in your system are impacting how schools make decisions concerning the 3 questions above. Three areas of work are briefly outlined below that enables you to do this:

- Curriculum provision and guidance

When it comes to curriculum and instructional resources, it is helpful to document what materials your system directly provides to schools and what guidance you provide to help schools choose the right materials. For example, some systems provide broad achievement standards and require teachers to backwards map the rest, some systems provide key assessment tasks, some provide unit outlines but not lesson plans and so on. By mapping what the system provides, you highlight what schools are required to do to develop (or choose) and then implement comprehensive teaching programs. This enables you to better identify areas of need and then target reforms.

So, when data from schools shows there is large variation in the instructional resources used in classrooms and poor quality texts being used, you can more quickly identify the appropriate policy response. If teachers say they need more help developing curriculum materials, then you can complement what you already provide. In one system we worked in, the system was providing a lot of instructional materials, but schools were largely ignoring them. This led to a response to improve access to the materials, document their use more systematically, and increase the focus senior and middle system leaders put on the materials in their interactions with schools.

- System expertise and development

The second area of work looks at the level and distribution of expertise in schools and across the system. We regularly talk about expertise in education but too rarely get to the specifics of what expertise school leaders and teachers access and how can it be improved.

The data collected from schools will highlight what expertise teachers are accessing. There will be variation in the data, but some consistent names will more than likely start appearing – a local math expert, a specialist reading support organisation, a popular professional development provider and so on. This enables you to review the most popular sources of expertise for schools. If they are good, and support the implementation of quality curriculum materials, instructional resources and assessments, then you can work with the expert and try and spread their influence. If they are not good, then you can use a variety of methods to incentivise schools not to use the low quality expertise

To complement the school-level data on what expertise is being accessed, is an activity that creates first, a system map of the expertise system leaders believe schools should access, and second, a process for helping schools access that expertise. This activity forces system leaders to develop a common understanding of expertise and has been very impactful in systems we have worked in.

The activity is focused on expertise in specific curriculum areas as normally, there are many generalists in most systems. So, following PISA, the activity identifies the experts that schools should access for specific problems in mathematics, science and reading. This activity must include the system leaders that work with schools. It involves four steps:

- Break mathematics, science and reading into their key stages or learning areas. So, if you are looking at primary/elementary school mathematics then you can break it down into, say, arithmetic and geometry or smaller categories like number and measurement.

- For each of these categories identify the expertise that schools in your system should access for support. So, if a primary/elementary school has a problem with student learning of arithmetic, which expert or experts should they access for support?

- Then write down the experts in each area for each geographical region – schools in one city may not be able to access an expert in another city and schools in remote locations often struggle to find experts.

- Reach agreement amongst your system leaders on the list of experts that they will recommend when a school from each geographic area has a problem in the relevant curriculum area.

I know this exercise seems basic, but we often talk about expertise in very broad terms. I have worked in systems that complain of a lack of expertise but then we are able to sit down and identify the people that either can be considered experts or can be developed into a network of experts over time. On the other hand, I also work with leaders who claim there is lots of expertise in their system but are then unable to name a reading expert who can help schools in a specific geographic location. This is why it’s important to actually write down the names of the experts/organisations that can help schools in each location. It forces you to be specific. You can then identify, and start to fill, important gaps in expertise in your system.

There is great value in system leaders discussing which people/organisations are and are not experts. It’s an important conversation to have; a system needs to have a common understanding of expertise and where it is, and is not, in the system. It enables highly efficient policy responses that target expertise where it is most needed

- Common approach to improvement

It is hard to overestimate the importance of developing a shared understanding of school improvement. Do people have a common understanding of what steps should be taken in schools to improve teaching and learning of science, reading and mathematics? If data from your schools show that there is not a consistent approach, or that school leaders and teachers are uncertain about what to do to improve teaching and learning, then introducing a common understanding of improvement in schools is a clear policy lever to lift performance. The same applies to the middle layer of system leaders. Many systems we work with do not have a common understanding of school improvement. This results in a lack of job clarity and increases variation of how system leaders interact with schools (meaning policy reform is presented in different ways to schools). This is confusing for schools, lowers the potential impact of reform, and prevents systemic improvement. Some of the best work we have done is working with system leaders to reach a common agreement on what steps schools should take to improve teaching and learning. I have discussed this improvement cycle here and will continue to focus on it in the future.

Identifying immediate reforms

The above steps can be taken relatively quickly and will identify reforms that can be taken to improve reading, science and mathematics through:

- Improved quality of instructional resources available to school leaders and teachers

- Guidance on selecting and implementing these resources in cohesive teaching programs

- Guidance on effective assessment practices in a school and for teachers within a subject area

- Evaluation of common professional development programs and targeting of effective and ineffective programs

- Providing expertise to schools who need it most

- More efficient development and use of subject experts across the system

- A more effective middle layer of system leaders

- Improved clarity on the steps school leaders and teachers need to take for improvement

When we have used this approach it has always highlighted important areas for systems to undertake immediate reforms. Of course, the precise reforms will vary with the system. These immediate reforms may not constitute large policy changes, but they have an immediate impact on schools.

Laying foundations for larger policy change

Through this approach we can build on immediate reforms to develop large policy changes. It is in the development of large policy reforms that the global policy discussion becomes most useful. We can compare policies in different countries, identifying what is most useful given the data you have collected about your own system.

I don’t pretend for a minute that the steps I have briefly discussed above amount to a comprehensive strategy. But it provides an immediate way forward and these steps are actually the building blocks of systemic reform.

I have researched and worked with high-performing systems around the world for many years. I have documented their policies, their strategic approach and how they enact systemic reform. What these systems share in common is that driving their policy reforms is an intense focus on continually improving teaching and learning of subjects of their curriculum. When we focus so much on high-level policy discussions, we are less likely to emulate the successes of high-performing systems.

Recent Comments