This is the first blog post for quite a while as the blogs I write didn’t seem appropriate with everything that has been happening. But I have regularly been told by system leaders that the work of school and system improvement never stops. So, I have decided to start the blog again, and will have regular posts through the remainder of 2020. This blog is not time sensitive so for the many people that are flat out dealing with Covid, hopefully this will be of use at a later date.

Virtually every system leader I speak to is worried about the lack of impact they are seeing from large amounts of recurring PD expenditure; the research is clear that PD is not improving practice in classrooms across systems. We all know that in the next few years, government budgets are going to become very tight; large recurring expenditures with little or unproven impact will be prime candidates for budget cuts. I believe PD is essential to improving school systems; every high-performing system has had effective PD as a driver of performance growth. But I fear that PD budgets will be slashed if we can’t show that PD is making an impact.

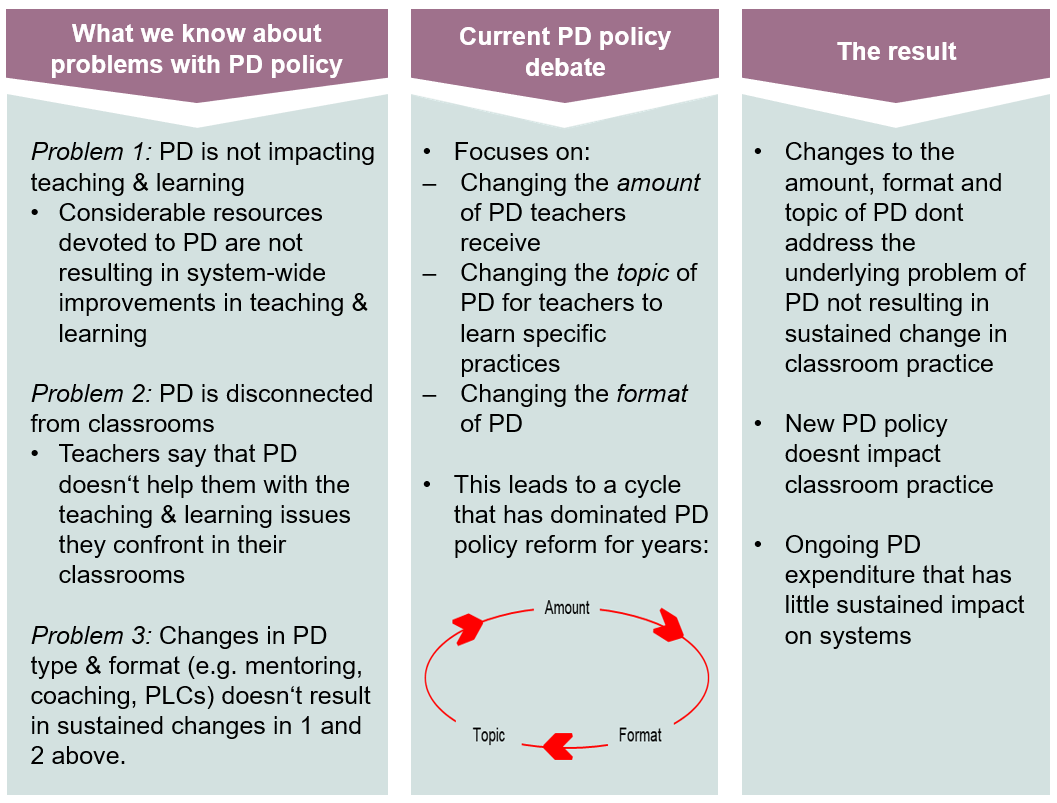

To achieve this requires a significant shift. Unfortunately, when we develop PD policy we often repeat the same mistakes, resulting in ongoing problems never being properly addressed. The Figure below illustrates All Poststhis by highlighting the three main problems with PD policy: first, the evidence shows that PD is not impacting teaching and learning at scale. Second, teachers report that the PD they undertake is disconnected from their classroom. And third, the changes we have made to the format and type of PD over the years don’t make that much of a difference to the first two problems. (See this blog for more discussion on the research and policy behind this)

As shown in Column 2 in the Figure above, these problems are not the focus of most PD policy debates. If you look at PD policies and how they changed over the past decade or so, the focus is nearly always on the amount, topic or format of PD. There is considerable research on these issues with many case studies showing that specific types of PD have had an impact in a school or group of schools. But the research is clear that these changes don’t have an impact at scale; they don’t address the underlying problem of PD not impacting teaching and learning in classrooms on a sustained basis.

An effective approach

A new approach is needed that follows the steps of high-performing systems. Previous blogs have described four steps to improve PD policy:

Step 1: Understand and clearly define the problem with PD policy: What is the problem with PD policy that we have to address?

Step 2: Define policy objectives: Is the current goal of PD policy to improve student learning of the curriculum?

Step 3: Be clear on what people need to do to improve: Is there clarity on what people need to do to ensure PD is effective in their school?

Step 4: Structure data, monitoring and evaluation to ensure learning of what is (and is not) working and to simply reinforce what people need to do to improve.

There is nothing particularly ground-breaking about these steps – for example, you will find them throughout all of the strategy literature – so how are they different from the usual PD policy debate? Let’s briefly break them down.

Step 1: Understand and clearly define the problem with PD policy is far from radical thinking but it strikes me that I rarely see detailed analysis of how PD programs are and are not working in a system. The fundamental problem is that PD is not changing practice at scale and we need to be honest that this won’t change simply by implementing PLCs instead of workshops, or coaching instead of mentoring.

Step 2: Define policy objectives. Given the problem with PD is that it is not addressing the teaching and learning problems teachers face in their classrooms, then the objective must be improving classroom practice at scale. But this is a broad objective that can take people in many directions when what we want to do is more closely target classroom practice. To do this we should focus PD on what is taught in classrooms; to make the objective of PD policy to improve teaching and learning of the curriculum used in the system. We have talked about the importance of linking PD to the curriculum in a number of reports. It forces PD to be more specific – to target specific teaching and learning in classrooms – and makes evaluation of the impact of PD much easier.

Step 3: Be clear on what people need to do to improve follows the fundamentals of good strategy. After you set clear and precise objectives, people need to know what to do to achieve them. Virtually every high-performing system in the world has used some form of an improvement cycle (or inquiry cycle if you prefer that terminology) to provide clear steps and role clarity for people in schools and across the system to improve practice to reach system objectives. Previous blogs have described a process to undertake this work (see here and here).

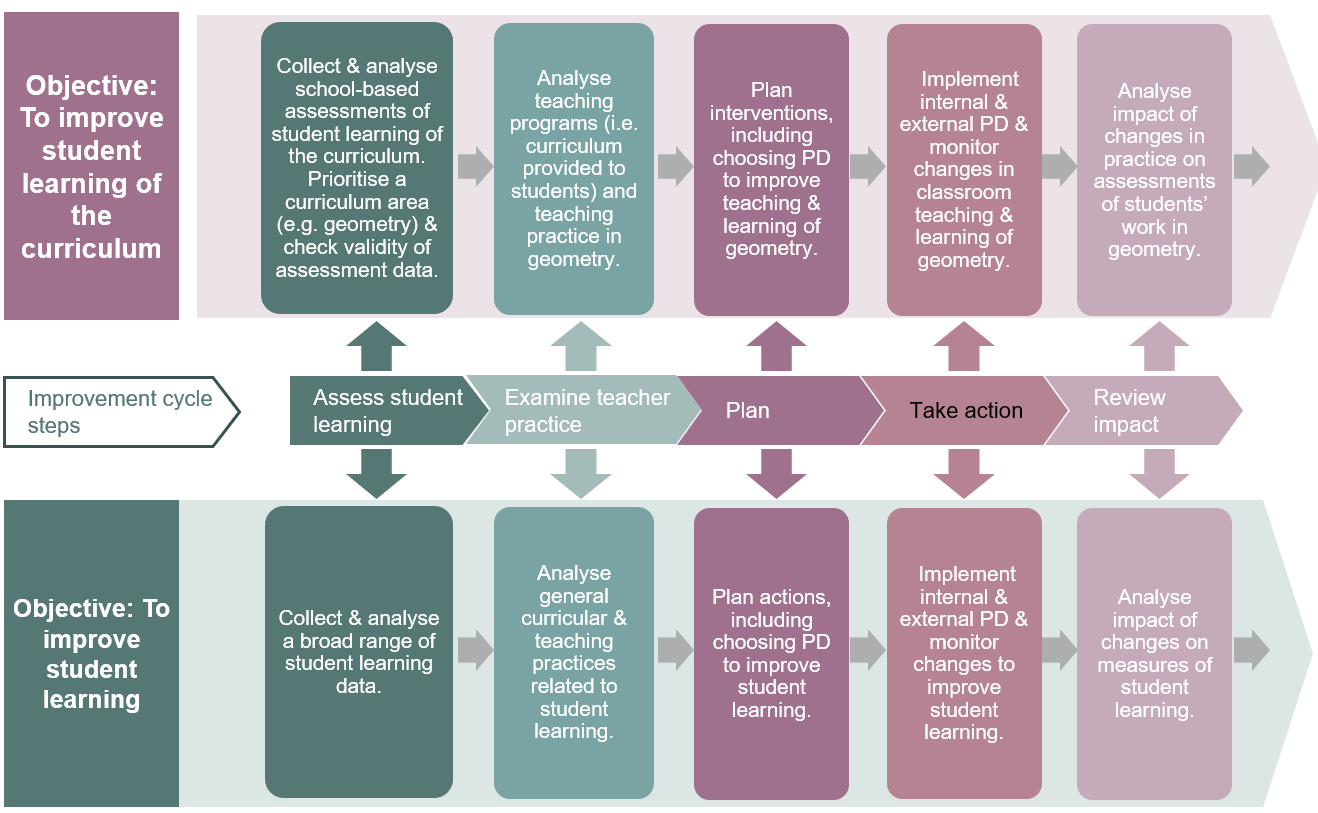

Steps 2 and 3 reflect the fundamentals of the literature on strategic change. It can be helpful to think of a strategic objective not only in what we ultimately want to achieve, but in how it sets parameters for decisions to be made and actions to take and not to take. The below Figure illustrates the potential impact on key decisions and actions in schools from setting a broad objective (student learning) versus a narrower strategic objective (student learning of the curriculum). Five stages of an improvement cycle are used to frame the sequence of decision-making and actions in schools based on broad or narrow objectives.

The sequence of decisions represented in the bottom half of the figure reflects the evidence on the problems with PD policy. They are more likely to lead to high-level PD that is disconnected from teaching and learning in classrooms; data analysis that is broad and results in ambiguous monitoring and evaluation.

In contrast, the narrower strategic objective on specific curriculum areas immediately anchors teachers’ and school leaders’ decision-making on which PD to choose, and how to implement and evaluate that PD, in data on teaching and learning of the curriculum in their school.

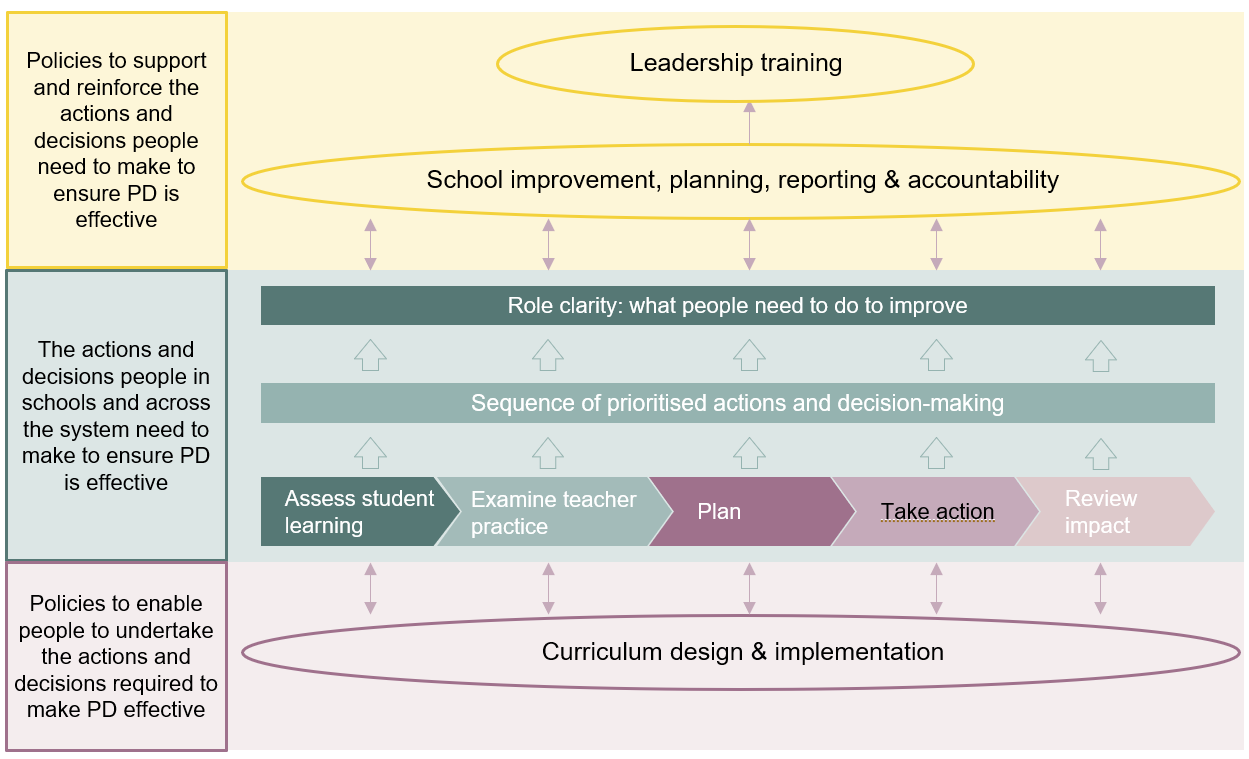

Step 4 Structure, data, monitoring and evaluation that is needed to support and reinforce the practices required in schools. School planning and reporting is the simplest and most effective way to do this as it codifies the decision-making and actions required for effective PD. This is discussed in a previous blog and illustrated below.

The below Figure also highlights that with most systems we work with, the way in which curriculum policy interacts with PD policy to enable improvements in teaching and learning needs to be understood and improved. For example, if schools have poor in-school assessment practices teachers can not accurately prioritise an area for improvement or monitor changes over time. And no amount of PD can improve student learning if instructional materials are poor quality or not appropriate for the grade being taught.. So, if a system wants better PD, then it needs to first understand curriculum implementation in schools and how this impacts decision-making and actions on the choice, implementation and evaluation of PD in schools.

This can make PD policy reform appear very difficult and large. But if we work through the four steps in this blog, we can identify specific policy interactions that make reform more tangible and achievable; it is not about changing everything.

To illustrate, let’s consider an example of a system that in step 1 finds that PD is not improving classroom practice and their teachers say that PD is not strongly linked to what they do in classrooms. System leaders are worried about this, especially as the system has clear objectives for mathematics and literacy.

Therefore, in step 2, system leaders make it clear that the objective of PD is to improve student learning of the mathematics curriculum. Leaders undertake a short review on current mathematics practice in classrooms including the instructional materials being used, the pedagogy implemented, and assessment practices utilised. They also run a survey and case studies of schools to analyse current PD to see if they can build on the good practice identified. System leaders use this analysis to both prioritise areas of improvement for PD policy, and to provide a baseline for data and evaluation.

In step 3, system leaders publish a clear, detailed guide for school leaders and teachers on what they need to do to effectively select , implement and evaluate PD in their school using the improvement cycle to improve teaching and learning of the mathematics curriculum. This provides role clarity and steps for key elements such as the formative and summative assessment data to be analysed and monitored, potential priority areas, and recommendations for quality PD programs and instructional materials (where possible).

In step 4, data systems and an evaluation framework are developed that uses the data discussed in step 2. This would include how well the improvement cycle is being implemented, but concentrate on changes in instructional materials being used in schools, and improvements in pedagogy and assessment practices. School-based assessments of the mathematics curriculum and system-wide standardised numeracy assessments, such as NAPLAN and PAT-M, provide data on progress towards the ultimate objective.

This is a very brief illustration of how specific interactions with other policy areas can be identified and then acted upon. In this case, PD policy needs to interact with curriculum policy through the assessment data used to prioritise, monitor and evaluate the impact of PD, and also through improvements in the instructional materials and related pedagogy and assessment practices used in schools. PD policy interacts with broader data and evaluation frameworks through data collected on teaching and learning of mathematics. This will become more systematic if integrated into school improvement planning.

Currently, many systems don’t have the data to evaluate the impact of PD. This approach allows us to do that, and to better identify improvements over time. This can lead to real improvements in classrooms. It can also provide the evidence necessary to protect and improve PD through an era of budget cuts.

Recent Comments