When the last PISA results were released in December, I wrote a blog post on how systems should respond to the results by shifting their strategy to what happens in their classrooms. I argued that they should make a proper diagnosis of the strengths and weaknesses of teaching and learning in specific subjects in order to develop actions for improvement.

My post didn’t cover all that a comprehensive strategy needs, but it generated a lot of discussion (hear this episode of Mark Scott’s Every Student Podcast, for example). And I was reminded of this last week when Ross Fox, Director of the Canberra and Goulburn Catholic school system said to me: “We don’t need another framework. We need efforts to make teachers’ work easier and that improves classroom practice”. Ross has spent many years working in large and small systems across Australia. He now leads a system of just under 60 schools in metropolitan and regional areas. I have known him for many years and know how much he wants to make a difference in children’s lives. He was speaking with the frustration of someone who has seen so much of his, and his colleagues’, hard work lead to little impact. His frustration is shared by many education leaders. Once the policy making wheels get in motion, we somehow find ourselves drifting further and further away from classrooms.

We can end this frustration. But only if we understand the reason behind it; the forces pushing policy away from classrooms. It is not something we talk about often, but the dominant strategic approach in Australian education – and in many countries around the world – is fundamentally flawed. This strategic approach means that system leaders, school leaders and teachers keep working harder and harder without seeing results.

Around the world, it is remarkable how similar education reform strategies are and how little they have changed over the years. Similar strategic approaches have been pursued in the great bulk of systems that, over time, haven’t made much progress in student learning, as shown in assessment data. These systems can differ in size, history and complexity, but the more I look the more I see a similar approach to strategy. There are two dominant features of this strategic approach:

- Policy lever approach

- Differentiated policy approach

Over time, these approaches have come together in some systems – while there are distinct aspects of each approach, the lines between them are blurry. Importantly, both fail some basic fundamentals of effective strategy. This and future blogs will work through these failures, how to remedy them, and how to create a new more effective strategic approach.

In short, the policy lever approach, popular across the OECD, focuses on the policy levers that the research says improves performance and also adds key objectives that system and political leaders want. So the strategy might stress teacher quality and better school leaders, then emphasise community engagement. The strategy will therefore have goals for world class teachers, the best school leaders, strong and vibrant community relationships, and so on.

The differentiated policy approach divides schools into performance categories, then allocates policy initiatives to each. It also emphasises policy levers, such as teacher and leader quality, but includes frameworks and data systems to categorise schools, first on student outcome data, then in areas such as community engagement, investments in teacher quality, leadership and so on.

I will write more on both strategic approaches in later blog posts, but here I will focus on why both approaches fail to sustain improvement.

Strategy research and use in other industries

I have been analysing the broader research on strategic reform and how it plays out in other industries. I want to share some passages from a book that leading corporate consulting firms also recommend, Richard Rumelt’s Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The difference and why it matters, encapsulates the mistakes that prevent so much education reform from having an impact on classrooms:

Many people assume that a strategy is a big-picture overall direction, divorced from any specific action. But defining strategy as broad concepts, thereby leaving out action, creates a wide chasm between “strategy” and “implementation.” If you accept this chasm, most strategy work becomes wheel spinning. Indeed, this is the most common complaint about “strategy.” Echoing many others, one top executive told me, “We have a sophisticated strategy process, but there is a huge problem of execution. We almost always fall short of the goals we set for ourselves.” …… A good strategy includes a set of coherent actions. They are not “implementation” details; they are the punch in the strategy. A strategy that fails to define a variety of plausible and feasible immediate actions is missing a critical component.

Bad strategy is more than just the absence of good strategy. Bad strategy has a life and logic of its own, a false edifice built on mistaken foundations. A good strategy defines a critical challenge. What is more, it builds a bridge between that challenge and action. A strategy is a way through a difficulty, an approach to overcoming an obstacle, a response to a challenge. If the challenge is not defined, it is difficult or impossible to assess the quality of the strategy.

The passages show that for a strategy to be effective it must link:

Strategy fails when these linkages break down, creating a “chasm between strategy and implementation,” when “most strategy work becomes wheel spinning.” This strategic failure is the frustration so many of us feel.

Strategy development regularly fails at the very beginning, when poor problem diagnosis means the challenges and obstacles critical for success are not identified, making it impossible to develop strategic actions to overcome them. In the corporate world, this occurs when strategies are based on outcomes such as trends in profit and market share, without proper analysis of the internal or external challenges that are driving those outcomes.

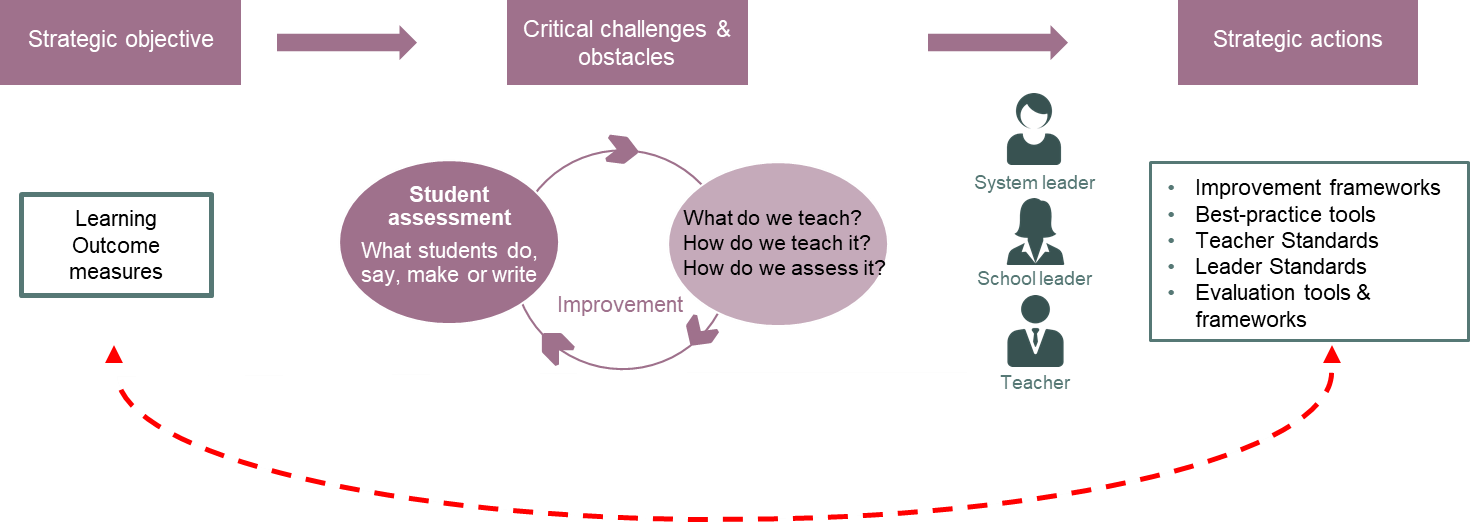

In education, identifying critical challenges and obstacles can generally be boiled down to how teachers and school leaders answer the three basic questions in any school: What to teach, how to teach it, and how to assess it? That is, the curricular choices, pedagogical strategies, and formative and summative assessment practices employed in schools. Improvement comes from how well people learn from the impact of their answers to these questions.

An effective education strategy therefore identifies critical challenges and obstacles in how well these questions are being answered in schools. Strategic actions are then developed to overcome these challenges and obstacles. Unfortunately, most education strategies fail to properly diagnose what is happening in schools; the key challenges in how schools are responding to the fundamental questions of what to teach, how to teach it, and how to assess it. This strategic mistake generally plays out in two ways:

First, strategy is too often developed from an analysis of outcome measures – usually standardised test scores. This reflects the common strategic mistake made in many industries discussed above.

Second, instead of diagnosing the challenges and obstacles that need to be addressed in schools and classrooms, an assumption is made that improvement can be driven from the development and use of best-practice resources.

Australian strategic reform: An example

I want to provide an example from my home country where the dominant strategic approach illustrates both of these mistakes. There has been relatively little problem diagnosis of what is happening in Australian classrooms; we have little data on the fundamental questions of what is taught in schools, how it is taught or how it is assessed. Instead, there has been a focus on analysing outcomes measures, and a huge growth in best-practice resources.

The past 15 years of Australian education have seen the development and extensive use of national teacher and school leader standards, improvement and evaluation tools, rubrics and lists of evidence to guide policy and practice. Teachers and school leaders, system leaders and policies have all been evaluated and recognised against these best-practice resources.

Little of this has been based on the critical challenges and obstacles faced by teachers and leaders in schools. As depicted in the Figure below, the strategy has skipped over the challenges and obstacles faced in schools and classrooms. It should not be too surprising therefore that the dominant strategy in the country has not led to improvements in classrooms. For example, Australia is one of the few countries in the world where students perform significantly lower in PISA than they did a decade or so ago.

Let’s consider how teacher or school leadership policies are developed under this strategy. The policies start with a general aim to raise teacher quality or create a more effective workforce. Because critical challenges and obstacles in schools are not identified, strategic actions focus on the use of, and improvement against the standards, tools and frameworks that are deemed most important. For example, the goal of a strategic action may be to have more teachers meet higher levels of a teacher standard.

The policy will then provide training and PD that is designed and evaluated against the prioritised standards and frameworks. In Australia, most PD is developed and evaluated against the national Teacher and School Leader standards. Data systems and evaluation frameworks will track the amount of PD undertaken and the percentage of teachers and leaders meeting various criteria against the standards and other evaluative tools. More schools may use specific lists of best-practice pedagogies, or more teachers may be assessed as ‘Highly Accomplished’ against the national teacher standards, and so on.

The strategic approach pushes policy development to focus on the right-hand side of the figure above, ignoring what actually happens in classrooms. While this is a clear strategic mistake, the popular narrative in Australia is that the failure to impact classrooms is due to poor implementation.

But if you look at the strategic actions emphasised, implementation has actually been effective. Australia now has:

- Hundreds of teachers assessed as achieving the highest level of the national teacher standards

- Thousands of teachers and leaders who have completed training and professional development programs that are developed and assessed against the standards and improvement tools

- Thousands of schools evaluated against these tools and rubrics

- More recently, evaluated systems against these tools and rubrics.

It is a noteworthy record of achievement except in the one place it matters: the classroom. This will not change unless we recognise the strategic mistakes made; if we keep pretending this is a result of a failure of implementation.

This is obviously a crude description of policy development but it illustrates how fundamental strategic mistakes push policy away from challenges, obstacles and outcomes in classrooms. And to be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with developing standards, tools and frameworks of best practice. The fault lies in the strategic approach that results in the choice, development and use of frameworks and tools that are disconnected from what is needed in classrooms. This problem is magnified when strategic objectives are subject specific (e.g. objectives to improve learning outcomes in a mathematics strategy). We will discuss how to overcome this problem in a future blog post.

While I have used Australian education as an example, these strategic mistakes plague many systems around the world. But there is a better and simpler way forward; there are plenty of successful examples around the world that make reform less complex and more effective. High-performing systems provide numerous examples. Some school districts in North America are fantastic at connecting with schools. And Australian systems have had success when they have ignored the dominant strategic approach. I believe there is now a growing group of system leaders pushing towards the classroom rather than away from it.

But we will only move forward if we acknowledge – and don’t keep repeating – the strategic mistakes holding us back. In future blogs we will work through how we can do this, with tangible examples people hopefully find useful.[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Recent Comments